V for Vendetta: anarchy vs. democracy

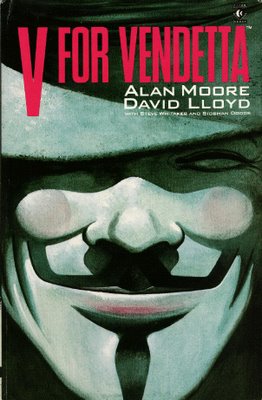

Dystopian futures in fiction often spring from conflict in society. Whether consciously or not, the writer taps into some vein of discontent and dissatisfaction that runs through the culture of the time and translates it into a skewed vision of the future. Often, this results in a vision of a totalitarian or authoritarian government, and the conflict that ensues from the struggle between concepts such as "personal freedom" and "security." V for Vendetta, written by Alan Moore with art by David Lloyd, is no exception to this. First published in the early 1980's, it was originally released in serialized "chapters" in Warrior, a UK magazine, and later picked up for re-release by the American publisher DC Comics. DC has since collected the entirety of the story in a trade paperback that is released under its "Vertigo" imprint, which is used for such non-superhero (and mature reader oreinted) works such as Neil Gaiman's Sandman and Preacher. In 2005, an adaptation was filmed for Warner Brothers studios (who own DC Comics) co-written and produced by Larry and Andy Wachowski, creators of the Matrix trilogy, and directed by James McTeigue. Released to theaters in March 2006 in the US, the adaptation was number one at the box office for its first weekend, and is generally considered to be a successful release financially.

The problems of adaptation arise when one attempts to translate a work from one format into another; in this case, from serialized sequential graphic art (or "comic book" form, as it is widely known) into a film format. The nature of the comic form brings with it unique problems from that of straight prose novels. The art of the piece lends itself to a very visual syle, which can benefit a filmmaker attempting to adapt it, as the "heavy lifting" of designing a visual look is done. But a large part of some comics (V for Vendetta included) is the juxtapostion of images on the page and the placement of the images within the individual panels. This is something that is less easily translated to film. Another of Alan Moore's works, Watchmen, which is considered by many critics and fans to be the Citizen Kane of comics, makes use of symbolic imagery and symmetry within the panel grid which would be impossible to translate onto film in any way. This is in addition to the normal problems of adaptation: anachronisms related to the time written versus the time filmed, plot points which work in a long form novel but which must be excised or compressed in a two-plus hour film, and themes which relate to the work as originally written but may not relate to the adaptor's view of what the work means. All these are in evidence in V for Vendetta the film, and all work to slightly change the meaning behind the story from that which Alan Moore originally intended.

One of the immediate changes made is that the film opens with a recreation and explanation of the Gunpowder Plot perpetrated by Guy Fawkes. The character of V's look, in both book and film, is supposed to be reminiscent of Fawkes, down to the mask he wears be a Guy Fawkes mask, so the sequence is not entirely out of place. The movie was made for American audiences, most of whom are not familiar with the legend of Guy Fawkes, and thus the connection between his actions (a plot to blow up Parliament) and V's planned actions is explicitly stated. The problem with this is that V's character in the book is NOT Fawkes-like, other than in his explosion of Parliament. In the book, V is an anarchist. He states as much, declaring his love of anarchy in a scene not in the movie, where he has a "conversation" with a statue of the lady Justice. He has a full back and forth dialogue with himself, representing both his own person and Justice, his former love, which culminates in his revelation that "there's someone else now . . . Her name is Anarchy and she has taught me more as a mistress than you ever did!" (Moore 40-41) He then leaves a small package, looking like the traditional heart-shaped box of chocolates, at the foot of the statue, which subsequently explodes. The last panel of the page is a close-up of V turning to the "camera", and saying "The flames of freedom. How lovely. How just.

Ahh, my precious Anarchy . . . 'O beauty, 'til now I never knew thee.'" (Moore 41) The end quote comes from Shakespeare's Henry VIII, act i, sc. iv. In his series of essays on the adaptation of V for Vendetta to film, Peter Sanderson refers to an interview with Moore where he stated "'I was just using Guy Fawkes as a symbol, without really any references to the historical Guy Fawkes. It was the bonfire night Guy Fawkes I was referencing, with the at the time easily available Guy Fawkes masks.'" Sanderson than goes on to state that "In Moore's series Fawkes thus becomes a symbol. If the fascists have taken over England, and the government has become the enemy, then Fawkes, the enemy of the government, becomes a freedom fighter. V impersonates a villain of British history, thus taking on the role of the devil, to fight for a noble cause." The film's connecting Fawkes so blatantly to V is thus not something intended by the text. In addition, the deletion of the Lady Justice scene from the story, and thus eliminating V's declared love of anarchy, takes out of the story one of the reasons V gives for blowing up Parliament, which is, as stated by Peter Sanderson, that "V seems to be arguing that this version of Justice has forfeited his allegiance by becoming linked with totalitarian rule; that is how he justifies blowing up the statue and the Old Bailey." The symbols of the old system (Parliament, the Old Bailey, Downing Street) must be torn down and destroyed, as does the system itself.

Another change, seemingly small, made to the text by the filmmakers is the age of Evey Hammond, the main protagonist, other than V, who is played by Natalie Portman in the movie. In the beginning of the book, Evey is 16, and attempting to solicit herself as a prostitute, as her income as a ward of the state is too meager to live on and she sees no other way to make money. Her naievety is apparent, as the first person she approaches turns out to be a "Fingerman," or policeman. The man, with his associates (also Fingermen), attempts to assault Evey, until she is rescued by V, who dispatches the men, including killing one with an explosive device, all while quoting Shakespeare's Macbeth. This begins V's arc of teaching, torturing, and training Evey, to the point that by the end of the book, she has taken his place willingly, in dress if not in method, and thus completes the book's statement of V as a symbol, undying and perpetually moving through history. She rejects V's passion for violence and death, but embraces his cause of anarchy and self-guidance. The movie, though, moves Evey's age up a few years, making her in her early twenties. She works at a television station, and is, while not well off, living well enough to have her own apartment. She leaves her apartment to meet Gordon, a television personality, for a date, in defiance of the curfew that covers London. She is stopped by Fingermen, and the scene unfolds much like the scene from the book. The change of Evey's age means that, in the words of Marc Singer from his essay "V and Virtuality," "Evey is a more adult character now . . . more mature, less vulnerable, and not especially looking for a father figure anymore; she never quite helps V in any premeditated way (until the very end), even working against him at one point in a vain attempt to pry herself out of his clutches." Whereas Evey in the book is vulnerable, and a mess psychologically (not helped by V's tactics and treatment of her through the story), looking for guidance, Evey in the movie is going along just to get along. As Singer says, "that greater confidence means Evey can reject V in no uncertain terms after his worst crimes are revealed. This is more morally palatable for us and better for Evey, but it's worse for the plot as it means she never sticks around to learn the tricks of V's trade, or to denounce his methods once she does." The implication throughout the film (and in one scene, stated plainly) is that Evey loves V in a romantic way, one which is less muddled with abandonement and father issues. Whether this was a natural extension of the story that the filmmakers saw as necessary, or a concession to the American audiences apparent need for a love story in every film, one may never be sure.

As just stated, Evey in the movie is not shown to be carrying on V's legacy as an individual symbol. This spot is taken by the crowd scene towards the end of the film, where the people of the city are shown marching to Parliament wearing the Guy Fawkes masks, wigs, hats, and capes which are identical to V's. This scene is not in the book, and in fact the book has the people of the city taking part in a violent anarchic riot orchestrated by V as a crucible to turn London into the true anarchic society he sees as ideal. This change is enormous, and is fact shifts the focus of V's vendetta, plot and victory from that of a society based in anarchy to a reformed democracy. Towards the end of the book, when all of V's machinations near their climax, he leads Evey on one final tour through his home, the Shadow Gallery, all while discussing anarchy and its aims. "Anarchy wears two faces, both Creator and Destroyer," he says, "Thus Destroyers topple empires; make a canvas of clean rubble where Creators can then build a better world. Rubble, once achieved, makes further ruins' means irrelevant." This speech underscores V's view of anarchy as a creating element. V, in his pirate broadcast on the television station earlier in the book, castigates the people of England for bowing to the government for so long, and thus makes the anarchic riot justified, as in his view, it is the people taking back what was taken from them. The Chancellor, Adam Susan, is assassinated by a common person, a woman whose husband was actually killed by V. Thus is born a society based in anarchic principles, one in which elements are torn down, only to be rebuilt as better from within, which is carried through the end, where the people of London riot and overthrow the

fascist government which has oppressed them. We are never shown the end results, or the after-effects, as the book ends with the riot still in progress. The implication (or hope of V, rather) is that a self-governing society results, with every man representing himself. The film, though, has a different message. The Chancellor, Adam Sutler (played by John Hurt, in what must be a conscious parallel to his role in 1984), is killed by one of his own men, in a situation set up and witnessed by V. As said in an essay on V for Vendetta on the Howling Curmudgeons blog, "That's a reasonably significant difference, because it tends to say that an evil government's undoing is itself, with the result that you don't need to act, you can just wait." The masks and costumes worn by the crowd at the end of the film were sent out by V to the people, reinforcing this view that the change comes from elsewhere, not from within the self. The people can choose to act or not, yes, but the idea to do so came from elsewhere, and was orchestrated and takes place whether those people who received the costumes marched or not. The fact that they chose to en masse is irrelevant; V's pirate broadcast (fairly intact in the film) still applies, as the people have just supplanted one leader symbol (the fascist Norse Fire government) with another (V). The film ends on a note of hope, with the destruction of Parliament and the hopeful looks on the faces of Evey and Finch (a policeman who's arc in the book mimics V's, but in the movie is just V's opposite number of sorts), but it is a false hope, as the same uncertainty which is within the book's ending is prevalent in the film as well, just without the real change of the riot and power struggle taking place in London in the book.

These small changes effect the story in large ways, and there are many changes which have gone unstated as well. The target audiences of the book and film are slightly different, and the time in which each were written are of definite influence. The original serialized form of the book was written in 1981, and, as Moore states in his introduction to the graphic novel collection, "the historical background of the story proceeds from a predicted Conservative defeat in the 1982 General Election . . . It's 1988 now. Margaret Thatcher is entering her third term of office and talking confidently of an unbroken Conservative leadership . . . It's cold and it's mean spirited and I don't like it here anymore." The book was written in an environment of oppressive government and near fascism, which lends itself to the setting and feeling the story evokes. On the other hand, the film was made by American filmmakers in 2005, with the Republican government in charge of the US constantly redefining the powers of the presidency and getting the country engulfed in wars over abstract ideas and false promises. As film reviewer Devin Faraci of Chud.com says in his essay on the film, "It's shocking that a film like V for Vendetta, in which the hero can be described in no other terms but terrorist, has been made by a major movie studio, which is itself a part of a major, world-dominating corporation." The labeling of V as a terrorist in the film is a very deliberate usage, meant to evoke images of 9/11 and Al Quaeda in the minds of viewers, and the fact that V is, in most ways, justifiable in his actions can challenge people to perhaps rethink their views of those we automatically label as "enemies." This is where the film succeeds in its depiction. The book is about the triumph of anarchy over oppressive order. The film is about the power of the people's voice over the voice of the few in power, as exemplified by what is seen by many as the film's tagline: "People should not be afraid of their governments. Governments should be afraid of their people."