The dystopian society seen within George Orwell's novel

1984 is close enough to our own that the similarities can be frightening. It has influenced countless novels and films, perhaps more than any other speculative science fiction work (with the possible of exception of

Blade Runner, though that is more in the visual realm than thematic.) Some of these films include

THX-1138,

Equilibrium,

Dark City,

The Matrix,

V for Vendetta, and Terry Gilliam's film

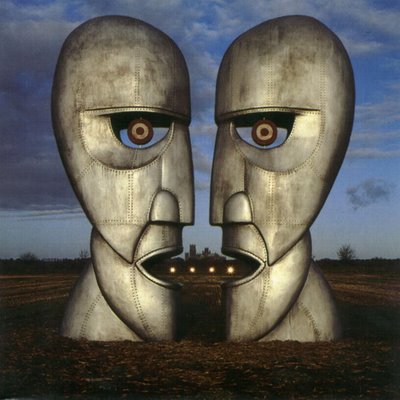

Brazil.

Brazil, while painting a picture of a slightly different society than Orwell's novel, hits many of the same themes, and parallels the novel's portrait of a society that has sacrificed freedom and privacy in the name of security. The differences are small, but profound, and are, with some analysis, indicators of where Gilliam's personal view differed from Orwell's.

1984

1984 is set in a dystopian future, where British and American society as a whole have been subsumed under the rule of the Party, the figurehead of which is the omnipresent Big Brother, whose stern gaze glares out from posters and signs everywhere one can look. There are constant reminders of the Party's Ingsoc (or English Socialism) philosophies in the also prolific signs proclaiming the slogans "WAR IS PEACE", "FREEDOM IS SLAVERY", and "IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH." Constantly at war with one of the two rival countries, Eastasia and Eurasia, while conversely allied with the other, the Outer Party members are kept subservient to the will of Big Brother and the Inner Party through the use of the techniques of "doublethink", and the application of "newspeak", the official language of Ingsoc. The Party itself is split into four main Ministries, which each govern a different are of society: Peace (war), Plenty (rationing), Truth (propaganda) , and Love (surveillance and interrogation).The members of the Party are constantly under surveillance, sex is forbidden except strictly for procreation, and with the proper application of newspeak, no Party member will ever have a thought that the Party would not approve of. In addition, the people are constantly reminded of an enemy in their midst, Goldstein and his Underground, who seek to undermine the Party, and cause terrorist incidents. The main character, Winston Smith, is a cog in the machinery of the Party, mindlessly doing his job, though he often thinks of rebelling. Eventually, he meets up with a girl, Julia, another Outer Party member who rebels in her own way, through sex. They maintain a secret room in an antique shop in the Prole section of the city. A series of events leads to Winston and Julia both being arrested by the Thought Police (the Party's instruments of order and intimidation), and taken in for interrogation and torture. During his torture (an attempt to "cure" him of his traitorous thoughts), Winston's superior, O'Brien, explains to him the true nature of the Party and the reasons for the endless war, as well as the philosophy of power for power's sake. Eventually, Winston's will and mind are broken down until he is practically destroyed, and the novel ends with Winston's realization of his impending death and that he now loves Big Brother.

Brazil

Brazil is set in a similar society to

1984, though the time is less distinct and slightly more anachronous. The title card states that it is set "somewhere in the 20th century at 8:49PM", and it takes place in an uncertain locale, as there are no landmarks or identifying characteristics that one can latch on to. The characters speak in many dialects, both British and American, and the technology is a combination of retro and futuristic. For example, there are computers, but instead of having large or fancy looking monitors, the prevailing tech is a small screen with a magnifying glass placed in front of it. The society seems to be more permissive than that of 1984, though the government is similarly split into Ministries, the Ministry of Information being the predominant one in the film, and where the main character, Sam Lowry, works. There are many terrorist bombings throughout the film, though they seem to be regular occurance, as people in a restaraunt continue eating though a bomb goes off on the other side of the dining room. Sam is a low-level worker who often daydreams of escapes and a mysterious "dream woman". These dreams form the most stunning visual aspect of the film, as they often intersect and play off what Sam has experienced or is experiencing in his life at the time. Sam's attempt to correct a mistake on the records leads to a convoluted series of events, including him meeting a woman, Jill, who is his "dream woman", becoming mixed up with the "plumber terrorist" Harry Tuttle, who works outside of government channels, and ends up with Sam being arrested and about to be tortured by his childhood best friend. He enacts a miraculous escape, with the help of Tuttle, and ends up battling through a nightmarish series of obstacles to be reunited with his love, Jill. At the moment when the audience believes Sam has escaped and everything is going to end happily, the rug is pulled out, as it is revealed that everything from the escape attempt on have occurred in Sam's head, and that he has escaped into insanity rather than be tortured and interrogated. He prefers the fantasy to reality.

One can see in the plot synopses that there are many surface similarities between the two works. Both take place in dystopian future societies, feature main characters who are small-time bureaucratic workers in their respective areas, both find "love", and both are captured and interrogated. The possibility is stated within

1984 that the terrorist activities, and even the missile strikes by Eastasia/Eurasia, are in fact perpetrated by the Party as a way to keep the population afraid and obedient; the same sentiment is in

Brazil, though not stated outright, that the bombings throughout the film are set by the government as a form of control. Here is where the movies diverge, though. Gilliam, in interviews about the film, has called

Brazil "1984 1/2" and "a 1984 for 1984", so the influence of the book on the film cannot be denied. What makes the difference here is Gilliam's sense of escapism. In Orwell, the only rebellion against the Party is actually a ruse perpetuated by the Party itself. In

Brazil, there is real rebellion and escape possible. The character of Harry Tuttle proves it, as he operates outside of the government's system, and is actually in a small way, the cause of Sam's capture. The ending of both novel and movie carry through on this thread. Whereas Orwell's novel ends with Winston Smith subsumed within the Party, awaiting death and aware of the love in his heart for that which he previously hated (Big Brother), Gilliam's film ends with Sam Lowry's figurative "escape" from torture and the reality that he despises into his own fantasies. This ending, which was one of the causes of Gilliam's well-documented problems with Universal Studios, is meant to be seen as a happy ending; Sam has won, he has beat the "bad guys" by not cooperating and not doing what they want. This essential optimism is what separates

1984 from

Brazil; where Orwell sees no escape from Big Brother, Gilliam says that one's mind is always a viable escape.

The difference in endings aside, both novel and film tell a similar story, and provide a similar warning to future generations on the dangers of sacrificing freedom for security, and putting too much power into the hands of those who claim to know what's best for society. One could say, "That will never happen here in the US, we are the free-est nation on Earth," but the seeds of it can be seen in the PATRIOT Act, and in the ease with which citizens have given up their personal freedoms and liberties in the name of "security" from terrorists. One hopes that people would be a little more careful.

1984 says that hope is pointless because Big Brother is always watching.

Brazil says that hope is in escape, and that is always possible.

Labels: books, film

The main difference, though, and the one from which a lot of minor differences can be extrapolated, is the choice of Hook (or, more likely, the producers who hired him) to make the boys on the island from an American military camp. The language and attitudes of the boys in the novel, especially towards the beginning, are steeped in the British school system of the time, and changing that element fundamentally changes the prior relationships of the boys. Ralph is no longer made leader due to his more "take charge" attitude (as in Brook's film), he's made leader because he already was one in the cadet corps. Jack, who is shown as more of a totalitarian leader-in-training in Brook, becomes the "bad kid" in Hook's, sent to military school for some unknown offense. This predilection to anarchy and violence in Hook's film makes his descent into tribalism and savagery less effective, as he was already that way before they ever came to the island.

The main difference, though, and the one from which a lot of minor differences can be extrapolated, is the choice of Hook (or, more likely, the producers who hired him) to make the boys on the island from an American military camp. The language and attitudes of the boys in the novel, especially towards the beginning, are steeped in the British school system of the time, and changing that element fundamentally changes the prior relationships of the boys. Ralph is no longer made leader due to his more "take charge" attitude (as in Brook's film), he's made leader because he already was one in the cadet corps. Jack, who is shown as more of a totalitarian leader-in-training in Brook, becomes the "bad kid" in Hook's, sent to military school for some unknown offense. This predilection to anarchy and violence in Hook's film makes his descent into tribalism and savagery less effective, as he was already that way before they ever came to the island. As said previous, there is good and bad in both films, but Brook's vision seems truer to Golding's original novel. Its such a product of its time and setting, that moving the story to a different era and millieu fundamentally damages the plot, and sends it off on tangents that do not benefit the story. Brook's film is the superior. What do you think, Stephen?

As said previous, there is good and bad in both films, but Brook's vision seems truer to Golding's original novel. Its such a product of its time and setting, that moving the story to a different era and millieu fundamentally damages the plot, and sends it off on tangents that do not benefit the story. Brook's film is the superior. What do you think, Stephen?